In his essay ‘On truth and lie in an extra-moral sense’, Friedrich Nietzsche argued that truth is nothing but ‘a mobile army of metaphors [. . .] coins which have lost their pictures and now matter only as metal’.1 While Nietzsche’s metaphor is itself difficult to follow (relying on a parallel between defaced coinage and a ‘dead metaphor’) his point is that metaphor is not merely a linguistic device, but one that underlies and structures the ways we think and behave. In a similar manner, Leora Maltz-Leca’s meticulously researched monograph attempts to excavate the metaphors underpinning William Kentridge’s studio practice, in order that we might better understand the unique currency of his work. In Maltz-Leca’s words, the book is ‘less an exploration of the textures, smells, and caprices of materials and making than a pondering of their philosophical dimensions’, positing ‘cutting and pasting, drawing, walking, and projecting light as metaphors for how we think and how we live’ (p.16).

Focusing on the ten films of the Drawings for Projection series (1989–2011) that propelled Kentridge to international fame, the book is structured according to the five metaphors that Maltz-Leca argues underlie Kentridge’s process: erasing, animating, processing, drawing (up) and projecting. The first chapter explores how erasure is used as a metaphor for both censorship and forgetting in Kentridge’s early work. Firmly situated in the political context of South Africa’s State of Emergency (1985) and the Sharpeville and Soweto Massacres (1960 and 1976), Maltz-Leca also provides personal and philosophical grounding to Kentridge’s method. For example, with reference to his parents, both prominent anti-apartheid lawyers, Maltz-Leca contends that metaphor’s inherent slipperiness offered Kentridge ‘a way of arriving at knowledge that was not subject to cross-examination’ (p.39) or the strictures of rational logic.

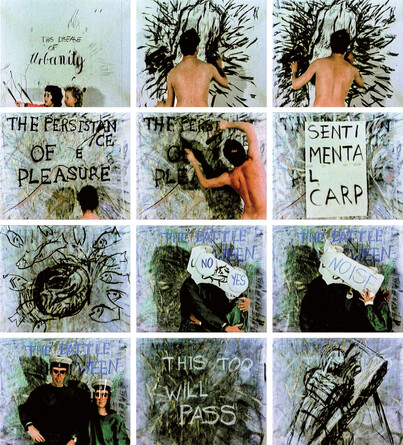

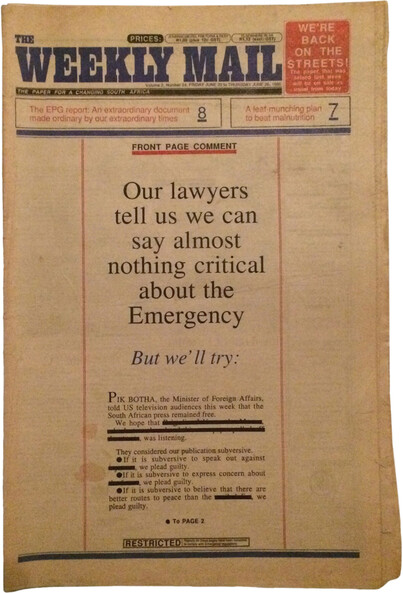

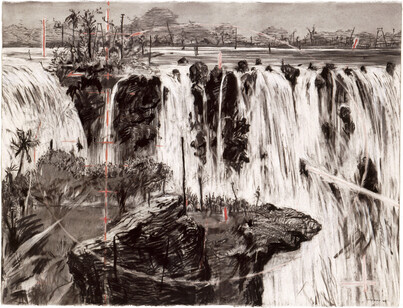

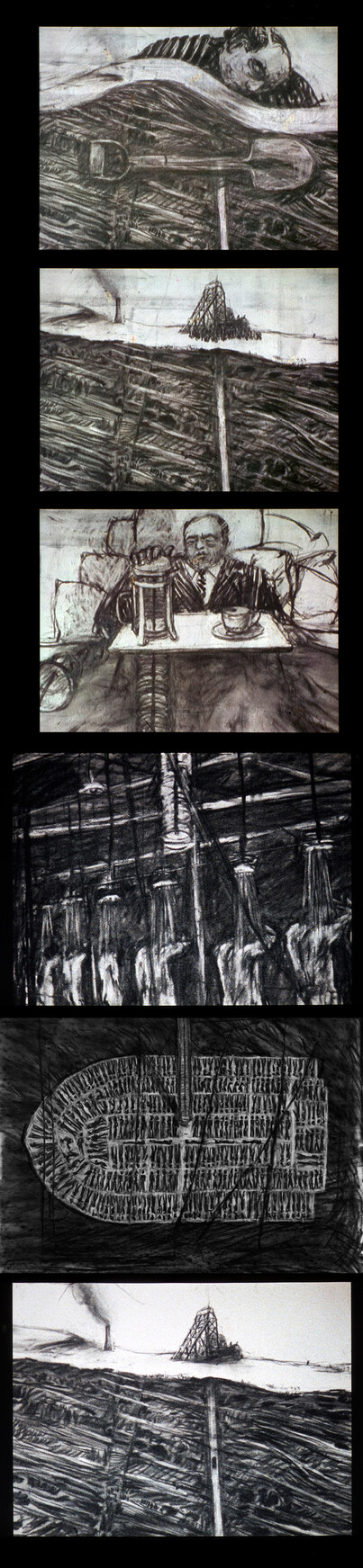

Through a study of Vetkoek / Fête Gallant FIG.1, in which Kentridge pioneered his use of animated drawing in 1985, Maltz-Leca explores his exploitation of metaphor to develop a politically engaged art that was neither instrumentalist nor didactic. Kentridge used a Bolex camera to photograph a charcoal drawing that he (and, in this instance, his family, friends and acquaintances) progressively erased and redrew, creating a time-consuming and unwieldy form of animation. Kentridge exploited charcoal’s grubbily ‘imperfect’ erasure, using visible deletion to draw attention to state censorship of the press. While purposefully blank spaces started appearing in newspapers in 1985 as a protest, eventually even these obvious redactions were banned as a symbol of subversion FIG.2 In the case of his Colonial Landscape drawings FIG.3, the red measurement marks of the theodolite (a surveying instrument) re-inscribe the traumas that have been erased from the landscape. Kentridge refers to these marks as ‘beacons against forgetting’ (p.75) in opposition to the landscape which ‘hides its history’ (p.70).

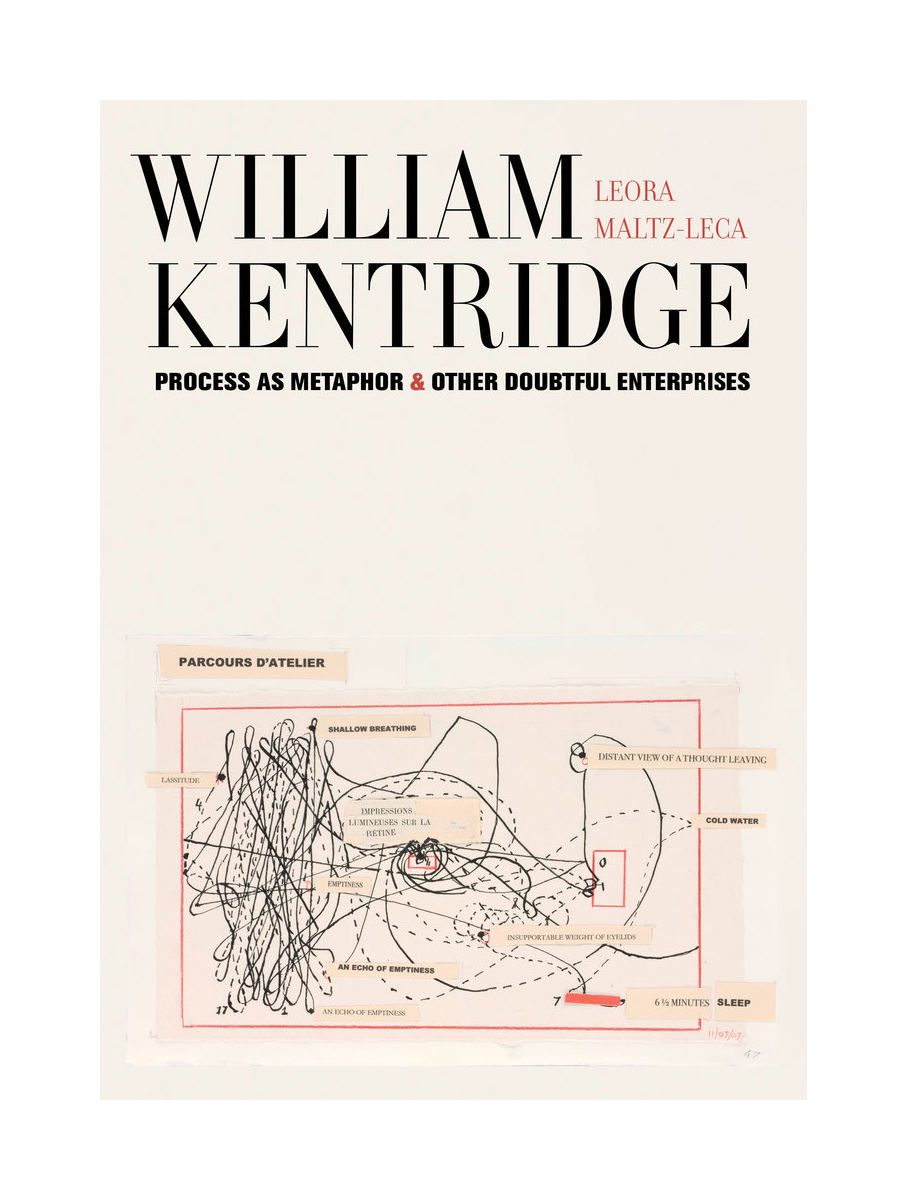

Maltz-Leca goes on to propose that both Kentridge’s animation and his ambulatory process (the way in which he paces between camera and drawing, mapped by the book’s cover image, Parcours d’Atelier from 2007), are steeped in ‘the country’s larger political processes of transition’ (p.13). Entitled ‘History as process, or chasing Hegel out of Africa: Animating’, the chapter examines Kentridge’s assimilation of Hegelian and Marxist philosophies of historical process. As Kentridge explains:

‘One of the ways things are false is when they get locked into being seen as fact, as opposed to moments of a process [. . .]. Looking out of the window now, I can see the leafy, wooded suburbs of the north part of Johannesburg [. . . But] this current, factual view is oblivious to how that wooded suburb was created’ (p.115).

Such an understanding was vital to the development of his ‘stone-age’ animation technique, and informed his particular response to the ‘frozen’ tradition of South African landscape painting in both his Colonial Landscapes and Drawings for Projection. Kentridge’s metamorphosing landscapes reject the tradition of eerily static and unpopulated vistas by artists such as Jan Volschenk and J. H. Pierneef, whose works embody the ‘exaggerated quietude of eternal truths and unchanging realities’ (p.120) that had long served colonial and apartheid myths of a terra nullius.

The third chapter focuses on the processions that wind through Kentridge’s work from 1989 – the year South Africa began its transition from apartheid to democracy. For the first time political protest marches (which had previously been banned) surged through the streets, enlivening a new iteration of an ancient form for the artist, detailed from Roman friezes to Renaissance triumphal arches. The scale and format of the Arc / Procession drawings – depicting a curve of waltzing, stumbling figures arching across sheets sometimes three metres wide – force a temporal reading of a static image. One hangs in Kentridge’s own staircase to prompt just such a mobile viewing. A comparison of his work with graphic posters and archival photographs of the period, including the choreography of Nelson Mandela’s ‘long walk’ to freedom, vividly underscores the imagery’s grounding in the context of graphic protest.

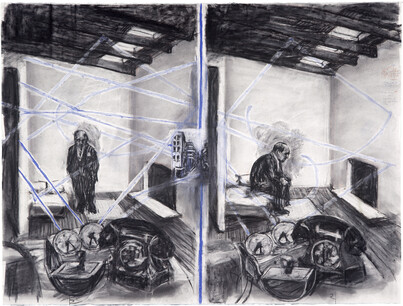

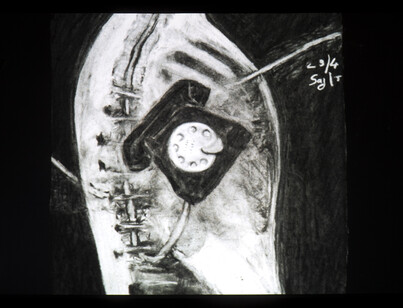

Kentridge’s post-apartheid work is examined alongside what Maltz-Leca calls his ‘epistemology of doubt’. Through close analysis of the works Stereoscope (1999) FIG.4 and Zeno Writing (2003), she examines drawing’s semantic origins as ‘drawing up’ and ‘drawing out’ (akin to the mining of psychoanalysis, where everything must be dragged to the surface for ‘processing’), as well as Kentridge’s use of electricity, telegraphy and telephones as models of the mind. Maltz-Leca also interrogates Kentridge’s ‘stereoscopic consciousness’. While a stereoscope combines two slightly different images to create one that appears three-dimensional, in Stereoscope, ‘the pairs of images never cohere, their gap paralleling the incoherence of a world that will not accord or make sense’ (p.221).

The final chapter examines Kentridge’s ur-metaphor of projection, both in the creation of his art and in its reception. Through the Freudian notion of ‘displacement’ – the shifting of anxieties and desires onto objects or people – Maltz-Leca examines Felix Teitelbaum and Soho Eckstein as Kentridge’s ‘displaced self-portraits’ FIG.5. Similarly she explores the way in which animated objects become proxies for the characters’ fear, guilt or trauma, such as the office paraphernalia lodged inside Eckstein’s body FIG.6. Projection is discussed through the extended metaphor of drawing as a ‘membrane’ where we meet the world – how much is the world, and how much do we project onto it?

According to Maltz-Leca, ‘critics have certainly noted Kentridge’s foregrounding of his working methods, although only Rosalind Krauss has broached the difficult question of why he does so’ (p.12). Metaphor as Process thus provides a welcome contribution to the scholarship on Kentridge’s philosophical and political conception of process, hitherto largely unaddressed. While the thematic approach can occasionally lead to a fugue-like recapitulation of works and motifs, it also provides the welcome opportunity to examine them from different perspectives. As well-chosen quotations affirm time and again, the specificities of apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa, rather than merely providing a backdrop for his work, actively shape every aspect of Kentridge’s formal understanding.

Maltz-Leca also effects a masterful realignment of his foundational artistic influences. Moving away from a narrow conception of a Euro-American lineage she highlights the deep debt owed to Soviet artists such as Dziga Vertov. Through the Junction Avenue Theatre Company in Johannesburg (which Kentridge founded in 1976 with Malcolm Purkey), Berthold Brecht’s method ‘shaped Kentridge’s investment in process in ways so fundamental as to go unremarked by the artist – and therefore unnoticed by critics’ (p.113). Maltz-Leca also explores the influence of Jacques Lecoq, the French actor and mime with whom Kentridge trained in Paris in 1981–82, and whose theories of embodied knowledge and gesture deeply informed Kentridge’s own. Maltz-Leca thus presents a formidable argument for Kentridge’s realignment in relation to global culture, providing us with an exhilarating image of what it means to be ‘contemporary up south’, and a more nuanced understanding of Kentridge’s unique body of work.