Postmodern pentecostalism: apocalyptic time in the paintings of Michael Stevenson

by Anna Parlane • June 2020

I think time is such a fundamental thing [. . . it’s] a kind of medium that we live in, and we all have a kind of foundational relationship [with it . . .] somehow in our childhood [. . .] I think you can’t get rid of that. It stays with you in lots of ways.1

Around 2010 there was a flurry of publications and presentations that aimed to theorise the period of ‘the contemporary’. Many addressed the nature of time and particularly the idea that time might be fractured, multiple or somehow non-linear. Instead of seeing it as the continuous and consistent background condition of our lives, these writers wondered if contemporary time might be different from other sorts of time, and if this difference might constitute a means of differentiating our moment of art production from earlier periods.2 Giorgio Agamben’s 2009 definition was typical: ‘contemporariness’, he argued, ‘is that relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism’.3 He proposed, paradoxically, that contemporaneity is achieved only by virtue of being somehow out of step with the time of the present. Pamela Lee, observing the fanfare around the launch of ‘the contemporary’ as our very own historical epoch, pointed out that a similarly complicated temporality was a key aspect of postmodernism: ‘We have yet to wrestle fully with postmodernism as an ersatz or partial theory of time, that for a while checked all the criteria of contemporary art’.4

This article brings what seems an idiosyncratic episode from a marginal art history to bear on this question of time in contemporary art. An examination of the early, under-analysed work of the New Zealand artist Michael Stevenson (b.1964) supports Lee's suggestion that postmodern temporality may merit closer scrutiny. Stevenson's religious art and particularly his expression of an eschatological worldview offers a significant point of origin for the fractured temporality of ‘the contemporary’. It also serves to complicate the too-tidy differentiation between contemporary art and its immediate predecessors. A view from small-town New Zealand in the 1980s demonstrates that these developments have been more protracted and diverse than is typically acknowledged.

Michael Stevenson is best known as the maker of intensively researched installations that range widely across late twentieth-century political and economic histories. Based in Berlin for the past twenty years, he is fluent in the codes of international contemporary art.5 As a young artist in New Zealand during the 1980s, however, Stevenson made faux-naive paintings of subjects drawn from the religious life of small-town communities. Although these works are little known, they were the artist’s first investigations into what Michael Taussig subsequently described as his interest in ‘a time out of time’.6

Pentecostalism and postmodernism in 1980s New Zealand

Stevenson’s paintings of the 1980s emerged from the collision of two apparently antithetical systems of thought in his life and work: Pentecostal Christianity and postmodernism. The paintings are depictions of church life in rural New Zealand. Stacks of Bibles or hymnals, FIG. 1 low-budget nativity costumes stored in cardboard boxes FIG. 2 and the interiors of empty, unadorned church halls FIG. 3 – the subjects of these works – were very familiar to the artist.

Stevenson is no longer religious, but he was raised in a Christian community in the tiny hamlet of Inglewood, Taranaki. During the 1980s his family attended the Inglewood Christian Fellowship, a church that purposefully lacks a clear denominational definition but which the artist has characterised as fundamentalist, evangelical and Pentecostal. The forms of Pentecostal and Charismatic spirituality that swept through Christianity from the 1960s and 1970s onwards were closely tied to the counterculture’s rejection of bureaucratic modes of power, and Pentecostal congregations in New Zealand in the 1980s typically gathered in humble community spaces reflecting this anti-establishment orientation.7 Pentecostalism rejects the grand edifices and rigid ecclesiastical structures of mainstream Christianity in favour of individual, direct and bodily experiences of contact with the Holy Spirit, and an eschatological conviction that such experiences signal proximity to God’s apocalyptic return to earth. The unusual temporality of Pentecostal experience results from this belief that the world is subject to the movements of an inscrutable and profoundly unpredictable deity.

In his study of religious change in Inglewood, Amos Muzondiwa described ‘the confusion brought about by the Pentecostal influence that hit Inglewood in the 1970s especially’.8 By the early 1980s a schism in Inglewood’s religious community, ‘driven’, as Muzondiwa relates, ‘by the new American ideologies and influence of global Pentecostalism’, had led twelve families to defect from the mainstream United Church to the Inglewood Christian Fellowship. These included Alan and Margaret Stevenson, who had for decades held leadership positions in the church, and their children. Alan Stevenson recalled: ‘We left dissatisfied with the lack of spirituality, the dryness of traditionalism and the frustrations of a church so rigid and change-proof one wonders if Christ equals rigidity’.9 The Stevensons were not alone in their attraction to a more dynamic and spirituality-centred faith. The religious historian Brett Knowles has described how ‘a powerful movement of the Holy Spirit emerged in the early 1960s’, inaugurating two decades of sustained growth for Pentecostal congregations in New Zealand.10 This corresponded with the movement’s phenomenal international success. While church attendance across mainstream Christian denominations has been in broad decline since the early 1960s, Pentecostal Christianity, alongside related Charismatic and Apostolic congregations, has ballooned, now numbering an estimated half-a-billion adherents worldwide.11

Alongside his religious life, Stevenson attended Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts between 1983 and 1986. He described it as a ‘crazy dichotomy [. . .] with two worlds on top of each other [. . .] I was going to prayer meetings at six o’clock in the morning, and then going to the painting studio and painting’.12 The two worlds of Stevenson’s religious and artistic pursuits seem, at first glance, utterly irreconcilable. While occupying a religious reality that continually affirmed his proximity to a powerful deity, he was also plunged into an artistic community in which a stance of ironic, sceptical disengagement was socially obligatory.

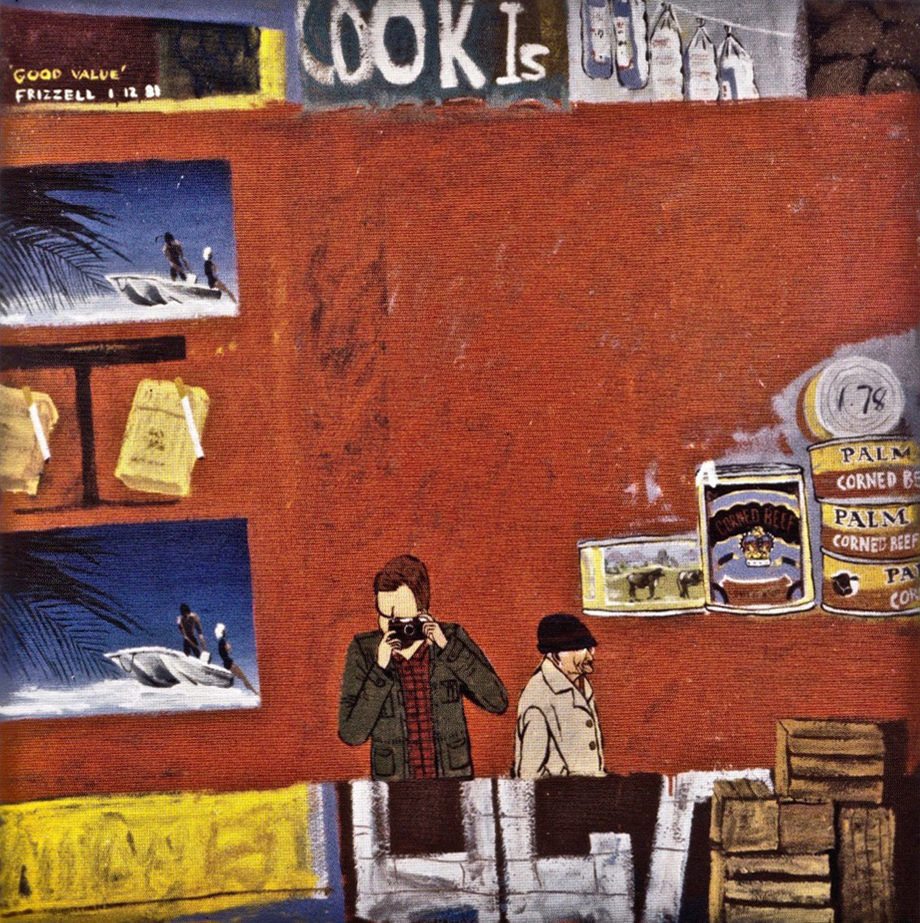

Stevenson’s teacher at Elam was Dick Frizzell (b. 1943), an energetic figure in Auckland’s painting scene who saw his practice in terms borrowed directly from the United States. Frizzell idolised Neil Jenney and understood his own work in terms of its alignment with New York ‘bad painting’, in firm opposition to the conceptual practices that were known in New Zealand as ‘post-object’ art.13 In the early 1980s, however, his work was pressed into the service of a local postmodernism that was quite different to international variants FIG. 4. The theories of Clement Greenberg barely warranted a mention in a New Zealand art history centred on landscape painting. ‘In a sense’, the curator Robert Leonard explained in 1992, ‘nationalism took the place of modernism in New Zealand. It provided the teleology, the master narrative, for local art history, just as modernism had (and does) in the Museum of Modern Art’.14 New Zealand postmodernism responded to this history.

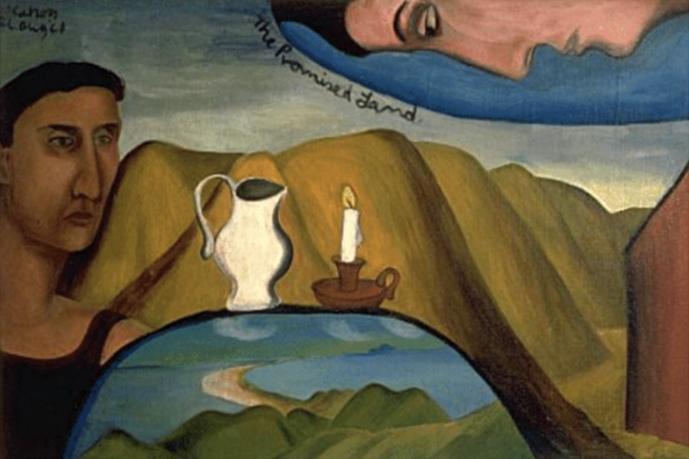

Throughout the twentieth century, New Zealand’s Pākehā (non-Māori) settler-colonials had struggled to forge a national identity half a world away from their cultural roots in Europe, while attempting to either suppress or absorb Māori claims to land and belonging. By the early 1980s the so-called ‘Māori Renaissance’ was building on a groundswell of land rights activism to position Māori voices prominently within mainstream cultural and political discourses. The nationalist master narratives of art history could not remain unaffected. While confident young Māori artists such as Michael Parekowhai, Peter Robinson and Jacqueline Fraser launched witty critiques of settler-colonial values, for Pākehā artists like Stevenson, postmodernism was synonymous with ironic post-nationalism. The efforts of such mid-century modernists as Rita Angus and Colin McCahon to wrest a sense of belonging out of the encounter between subject and landscape no longer compelled conviction. A way of relating to the New Zealand landscape that had once seemed profound was suddenly revealed to be superficial and inconsequential. Artists such as Julian Dashper, Ruth Watson, Ronnie van Hout and Judy Darragh reconceived the landscape as a kitsch readymade, an image borrowed from the tourist industry or generated using reproductions.

This narrative of New Zealand postmodernism took shape in the early 1980s. The exhibition New Image, curated by Francis Pound at Auckland City Art Gallery in 1983, presented work by Frizzell, Paul Hartigan FIG. 5, Richard Killeen and others that was Pop-influenced and steeped in irony.15 Pound argued that the primary interest of the work lay in the fact that it broke substantially from what he called ‘the old house and dead tree school of New Zealand painting’.16 As he later elaborated: ‘If landscape appears now [. . .] It is usable only in the form of a readymade – one would not paint it oneself [. . .] the archetypal genre of Nationalist art is touchable today only when sheathed in the prophylactics of quote marks’.17 New Image helped to formulate a local postmodernism characterised by its ironic disengagement from the New Zealand settler-colonial landscape painting tradition, and therefore, of course, utterly fixated on that tradition.

While Stevenson’s work can be differentiated from that of his peers by its religious aspects, his methods were distinctly postmodernist. At art school Frizzell and Stevenson found that they shared an interest in vernacular subjects and an enthusiasm for naive painting styles. Frizzell also taught Stevenson a methodology based on the quotation of found images: ‘He gave me an insight into how to go about the act of painting. Dick was very big on source material – you had to have a big stack of photographs in your studio, lots of books out of the library, bric-á-brac, postcards’.18 This quintessentially postmodern strategy would become central to Stevenson’s ongoing research-based practice, in which repetition, doubling and quotation are crucial tools. The quotation of existing material functions to displace the authorial voice, and as a young artist it enabled Stevenson to install a buffer zone of ironic distance between himself and his paintings. The resulting works were assembled from ‘source material’ largely consisting of snapshots taken by the artist on research trips. As he explained to his interviewer Anna Petersen in 1988, Stevenson’s naive style was similarly borrowed from artists as diverse as Horace Pippin, Christopher Wood, Cedric Morris and L.S. Lowry.19 His paintings are characterised by a self-contradictory tone containing both earnestness and irony, rustic charm and caustic humour. While their folksy style initially seems approachable, in the artist’s words, ‘rapidly after that first impression, the “Welcome” mat is snatched away’.20

Christmas Lights and Toilet Block FIG. 6, for example, hovers between sincerity and wry sarcasm. A night scene, the painting shows a small public park in which an enormous, slightly wonky timber cross supporting glowing lights strung up in the shape of a stylised Christmas tree has been installed next to a concrete block of public toilets. The Christmas lights, glowing ethereal white against a dark background of lumpy shrubbery, seem like a series of overlapping cartoon arrows pointing joyfully upwards as if to say ‘This way to God!’ The other sign in the picture, the one that reads ‘MEN’ and marks the toilet block entrance, has rather different connotations. In this little park, the sacred and the profane, cheerfully oblivious to their drastic incompatibility, co-habit.

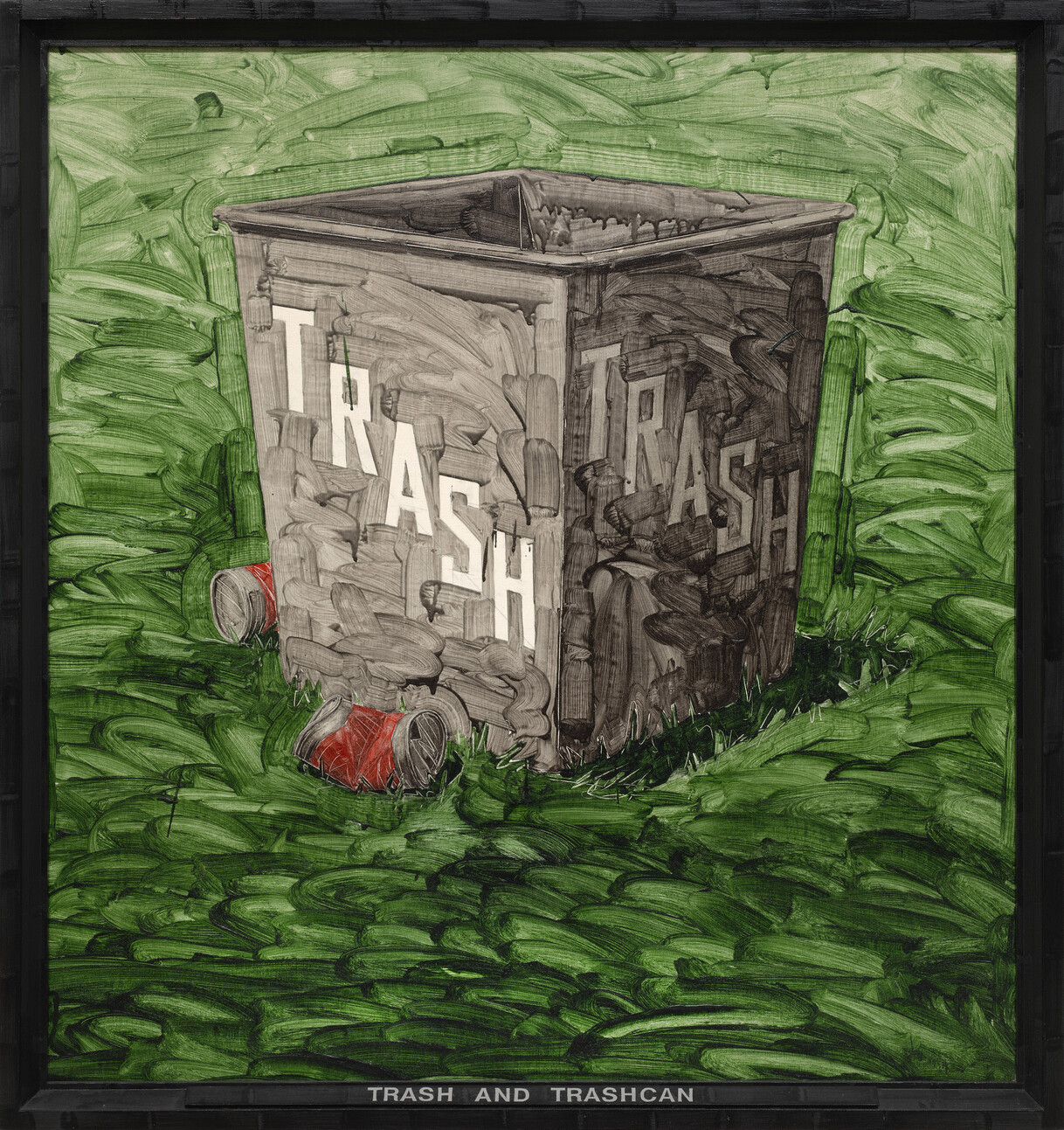

The ironic distance of these works, their purposefully clunky execution in conventional media and their vernacular subjects coalesce into a self-conscious datedness that can be aligned, alongside such artists as Frizzell, with the ‘bad painting’ trajectory of postmodern figurative painting. A great deal of the pleasure and humour of Christmas Lights and Toilet Block is due to the steadfastness of its pose as a naive rendering of plain fact, and our recognition that this is, in fact, a pose. Like the deadpan one-liners of Neil Jenney’s paintings, such as Trash and Trashcan FIG. 7, Stevenson appears to merely be quoting scenes from his own everyday life, conveying the fundamental absurdity of existence.

Misunderstanding Stevenson’s paintings

The presentation of religious subjects in Stevenson’s early works, however, endows them with a sincerity at odds with flippant postmodern quotation. Writers typically saw Stevenson’s paintings as conservative, melancholy and reverential, an impression assisted, it has to be said, by the artist himself. A statement from this time explains that his work ‘explore[s] details of small-town lifestyle that centre around the church hall and the public hall [. . .] For me these places have peculiarly spiritual references. Heaven smells of flower water, leached pine resins and old upholstery’.21 While writers such as Douglas Standring and Mark Amery recognised the enigmatic quality of Stevenson’s paintings, they also contributed to a broad consensus that these works were expressions of nostalgia for a faded provincial culture.22

In 1989 Stevenson showed in After McCahon, curated by Christina Barton at Auckland City Art Gallery. The exhibition explored local postmodernism’s complex relationship to the work of Colin McCahon, whose signature combination of landscape painting and religious angst had come to define modern New Zealand art.23 Barton’s theoretically sophisticated definition of New Zealand postmodernism as a post-McCahon condition built on Pound’s New Image. Compared to the existential drama of self-realisation playing out in McCahon’s works, she wrote that:

[a younger generation] bears witness to a profound scepticism. In this climate of critical disbelief, traditional claims to originality, authenticity, affectiveness and ‘self’ expression have been cast into doubt. As the ‘real’ recedes, dispersed by the mediating structures of language, in a plethora of surfaces; artists can no longer realistically search for some underlying truth, but instead, must find ways to articulate their new situation, without necessarily succumbing to it.24

Barton was poised, it seems in hindsight, to recognise the unusual combination of influences motivating Stevenson’s work and consider how faith might operate under conditions of postmodernity. However, at a time when the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement was busily disproving modernity’s secularisation thesis, the latter remained a ‘seldom-questioned orthodoxy’ in New Zealand.25 For Barton to enquire seriously about Stevenson’s religious beliefs would have been to upend the entrenched secularism of popular discourses in which faith, if acknowledged at all, was considered a private matter. She recognised the difference between McCahon’s faith and Stevenson’s, but did not challenge the prevailing view of Stevenson as a documentarian of small-town culture:

In Michael Stevenson’s paintings of small, undemonstrative brethren churches in the nowhere places of suburban and provincial New Zealand, the omnipresent but disembodied word of God is replaced by simple statements of belief spoken not by angels and saints, but in the words of ordinary people. Not I Paul to you at Ngatimote [sic] but Jesus loves us all: in Clinton.26

In McCahon’s I Paul to you at Ngatimoti FIG. 8, the prophet alights in rural New Zealand to proclaim his truth. In contrast to the epic proportions of McCahon’s faith, where Biblical prophecy echoes through the New Zealand hills FIG. 9, Barton framed Stevenson’s beliefs as unpretentious, community centred and pluralism-friendly. In short, even when they were recognised as religious works, Stevenson’s paintings were interpreted as humble and non-threatening, closer to community spirit than Holy Spirit. Something more like regionalism, in fact, which Francis Pound recognised when he reviewed the show. He publicly slighted Stevenson’s work by describing it as an uninteresting coda to McCahon’s canonical modernism. As Stevenson wryly recalled, years later: ‘Francis Pound’s wonderful line was: a neoregionalist footnote to McCahon that bears too much reference to Philip Guston and Morandi’.27

In after McCahon a narrative about New Zealand art’s connection to place (or its sceptical repudiation of the same) predominated and the relationship between postmodernism and Stevenson’s Pentecostal faith has remained unacknowledged. The centrality of arguments about place in New Zealand art history obscured the fact that Stevenson’s paintings are primarily about time and an unusual kind of religious time. As he reflected in 1996: ‘I was never trying to create “New Zealand Art”, although I was interested in the construct of New Zealand-ness. In fact, my early work isn’t representative of New Zealand at all, it’s more wacky Southern Baptist Hillbilly’.28

Pentecostal time

By considering Stevenson’s faith, and in particular Pentecostalism’s eschatological orientation – its expectation of an imminent apocalypse – we can see how these paintings articulate an unexpected convergence between Pentecostalism and postmodernism. Jesus Loves Us All: In Clinton FIG. 10 shows the interior of a church hall in Clinton, South Otago; the sort of unadorned hall used by Pentecostal congregations. A large banner – JESUS LOVES US ALL – hangs above the window, which opens onto a blank view, perhaps sky, perhaps the wall of a neighbouring building. This banner, with its affirmative message of Christ’s universal love, is directed inwards, towards the congregation, rather than to the strangely vacant outside world. Far from a description of a humble, non-threatening religious community anchored in a particular, recognisable place, this is a painting about religious exclusivity: Jesus loves us all (in Clinton). Stevenson describes a community, like that of his home town, operating at an intentional remove from broader society. He has described it as a ‘parallel world’.29 Believers are divided from their neighbours by their expectation of their own imminent salvation on Judgment Day, and, more pointedly, by their expectation of everyone else’s imminent damnation.

Many Pentecostal believers adhere to a premillennialist worldview, which means that their understanding of time is different to what might be termed secular time. Secular time is experienced as a perpetual process, ‘in which things happen but not to which things happen. It is steady and regular and supports a model of the world in which continuity is the default assumption’.30 In contrast, premillennialism presupposes a discontinuous time, in which the end of the world is, essentially, nigh. Believers expect that the time we currently occupy can and will come to an end, abruptly and possibly violently, when Christ returns to earth. As a result of this fervently anticipated divine arrival, ‘one temporal progression is halted or shattered and another is joined’.31 Expecting that the world-shattering rupture of Christ’s return could occur at any moment, Stevenson has described how believers occupy a position that continually trembles on the brink of apocalyptic revelation and the cessation of reality as we know it. Their faith centres on the belief that we are living in the end times and in anticipation of an apocalypse that is perpetually imminent.

The anthropologist Charles Piot has described how the prominence of the Christian end-times narrative in Pentecostalism ‘serves to condition congregants into an openness to a radical/millennialist orientation toward time’, which suffuses everyday life.32 The corollary of this permeation of millennial excitement through daily life is, of course, the sheer inertia of waiting for a future that is perpetually about to arrive. Stevenson has described it as exhausting: ‘people are held in this constant and very weird state, ad infinitum [. . . it] is just without end’.33 As Standring recognised, Stevenson’s paintings often exude a melancholy sense of loss or absence.34 For example, in After Christmas FIG. 11, a number of bedraggled party streamers hang from the ceiling of an otherwise unforgivingly functional church hall. The painting is dated 12th June, suggesting, perhaps, that the Christmas decorations have simply been left up from the previous year. However, rather than a narrative about small-town decline – as in Standring’s interpretation – the airless stasis of After Christmas might be better understood as commentary on a two thousand-year-long waiting game that has grown grim with fatigue and interminability. Viewed in terms of the endless endurance demanded by the expectation of the Second Coming, Stevenson’s painting could perhaps equally be titled ‘after Christ’. This sense of exhaustion is underlined by his practice of inscribing the day’s date onto the surface of each painting to mark the passage of time, like a child counting down until the school holidays or a prisoner tallying days of incarceration on the cell wall.

The inertia that pervades many of Stevenson’s paintings is also punctuated in many cases by clearly marked exits. The Church of Christ, Dominion Road (1987), One Baptism FIG. 12, Harvest Home (1988), Inside the Church Hall FIG. 13, all feature open doorways crowned by conspicuous exit signs. The doorway in Inside the Church Hall, for example, is positioned in the exact centre of the composition and exerts a magnetic pull: the banal interior seems to thrill with the possibility offered by this opening. It is also significant that the paintings do not typically show what is on the other side of these marked exits. As in Jesus is Lord, Interior FIG. 14, the open doorway is almost always dark or blank. Openings onto another space, or perhaps another time, they remain as yet unfulfilled promises. These exits stand in Stevenson’s paintings as a reminder of the divine intervention that could at any moment disrupt the fabric of reality, and supplant our temporal order with a wholly new one.

Rejecting the institutions of church and state in favour of allegiance to a God characterised by unpredictability and intensity, Pentecostal believers occupy a time perforated by signs and wonders: the opaque and miraculous messages of a deity who reaches in to our world from another dimension to signal that the end is near. The primary goal of Stevenson’s paintings is not to convey a melancholy message about the decline of small-town community life, nor do they describe a pluralism-friendly postmodern faith grounded in community spirit. They are not regionalist in any sense, least of all as a footnote to McCahon’s quite different worldview. They do share the postnationalism of the artist’s peers, but only insofar as Pentecostalism also operates at a remove from the secular nation state. The consistent message of Stevenson’s paintings is their articulation of Pentecostalism’s eschatological worldview.

Perpetual deferral in Pentecostalism and postmodernism

While Stevenson’s early work differs from the dominant mode of New Zealand postmodernism it should nevertheless be categorised as postmodern; it is also true that his paintings are primarily religious in nature. It seems, however, that religion should have no place in a postmodernism predicated on the denial of metaphysics. What possible relationship could there be between a religious worldview that so fervently anticipates divine revelation and a postmodern perspective that refuses any notion of a single or ultimate truth? The answer lies in the unusual temporality of Stevenson’s work. Both postmodernism and Pentecostalism create a state of perpetual deferral. Pentecostals look forward to an event that has been hovering in the near future for over two thousand years. When final resolution seems permanently out of reach, the reality we inhabit is defined by its temporary status. Postmodern art, according to Craig Owens, occupies a similar position: it also narrates its own ‘contingency, insufficiency, lack of transcendence. It tells of a desire that must be perpetually frustrated, an ambition that must be perpetually deferred’.35 Stevenson's works negotiate the gulf between a worldview centred on the perpetual expectation of revelation and a reality that endlessly divides to hold open multiple contradictory possibilities, creating a space of perpetual deferral, of expectation and dislocation that the artist has described as ‘boredom and madness’.36

The world described in Stevenson’s paintings is a world of stage props: low-budget, temporary stand-ins for the true reality to come FIG. 15. Created in a purposefully naive style, they are self-consciously poor representations of a reality that likewise could be thought of as simulacral, a dress rehearsal. Stevenson’s spartan church hall interiors register the intentional aesthetic poverty that is deeply linked to Pentecostalism’s anti-establishment nature FIG. 16. What Stevenson has called the ‘Pentecostal/Charismatic aesthetic’ is utilitarian and temporary.37 It makes do, using materials easily to hand; driven by urgency it is often roughly executed. If the ornate churches of mainstream Christianity represent an investment in this world, the Pentecostal/ Charismatic aesthetic reminds us that we are but travellers passing through.

The sly, faux-naive quality of Stevenson’s paintings is also essential to their postmodernism. As in the best of Frizzell’s paintings from this period, Stevenson’s vernacular subjects are treated with both genuine affection and cool irony. These loving renderings of small-town life plant the suspicion, never resolved, that the artist’s naivety is a parody, the painting’s earnest clumsiness is staged. Stevenson’s ability to hold an image in quotation marks, a skill imparted to him by Frizzell, dislocates the painting from its maker and therefore from the comfort of resolution: artistic intention is suspended between (at least) two contradictory possibilities.

In and around the 1970s, the art world and the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement responded to historical conditions in strikingly similar ways. Both developed into transnational, globalising networks of activity centred on the provision of individual experiences for their congregations. In Terry Smith’s formulation – which omits the term postmodernism while spanning its period – the shift from modern to contemporary art was ‘nascent during the 1950s, emergent in the 1960s, contested during the 1970s, but unmistakable since the 1980s’.38 In the 1990s a pantheon of entrepreneurial auteur curators – Catherine David, Okwui Enwezor, Hou Hanru, Hans Ulrich Obrist – and Pentecostal/Charismatic preachers – John Wimber, C. Peter Wagner, David Yonggi Cho, Enoch Adeboye – rose to prominence as the privileged prophetic voices of these new orders.39 Both postmodernists and Pentecostals had faced a world characterised by the default of structures of authority and a truth no longer accessible through traditional channels, but delivered unpredictably from elsewhere, if at all. In both instances, the result was a system of dispersed authority in which relational networks are prioritised over bureaucratic structures. The spectacular growth of Pentecostalism in New Zealand from the 1960s occurred in parallel with the counterculture’s rejection of institutional power in favour of personalised and individualised – or Charismatic – sources of authority.40 In line with postmodernism’s rejection of absolutes, the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement swelled with believers gravitating towards its freewheeling, dynamic and individualised style of worship. In the fractured temporality of a state of perpetual deferral, it seems that both postmodernism and Pentecostalism offered an alternative to established modes of authority.

The unusual temporality of Stevenson’s contemporary practice, the artist’s interest in ‘a time out of time’, has its roots firmly in postmodernism, and in a once-marginal (but now wildly successful) religious worldview that can also be understood as an articulation of the fractured time of 'the contemporary'. The collision of postmodernism and Pentecostalism in Stevenson’s life and thinking during the 1980s posed an intellectual problem that his practice continues to circle, decades after his departure from faith. The epistemological question of how we can attain knowledge of what remains, perpetually, beyond direct experience has operated as a constant irritant motivating his work, as it moves restlessly among histories of the recent past. Just as the globalism of ‘the contemporary’ took shape over a long period before emerging as one of the dominant conditions of our time, it seems reasonable to suspect that this is also true of the fractured and disjointed temporality that is its other key characteristic. A disjunctive relationship to time did not arrive promptly at the inauguration of ‘the contemporary’. It was part and parcel of an earlier period of postmodernism, in which dominant ideas about subjectivity, authority and our relationship to place were dismantled and a new mode of networked and dispersed authority, predicated on a fractured temporality of perpetual deferral, gathered momentum.