The Instagram counter-archive: Guadalupe Rosales, Graciela Iturbide and Chicana representation across borders

by Caroline Tracey • June 2021

A Chicana in Mexico City

In October 2019 the Museo Universitario del Chopo, Mexico City, invited the artist Guadalupe Rosales to give a presentation about her Instagram account @veteranas_and_rucas, a counter-archive of Southern California’s Chicana community.1 Dressed in black vinyl jeans, a white hoodie screen-printed with an adaptation of the Los Angeles Dodgers logo and a black cap, Rosales sat at the front of the museum’s makeshift auditorium with her knees spread, leaning forward to rest her elbows on them. She presented in English, apologising – ‘I only speak Spanish with my family and I don’t talk to them that often’ – but said she would take questions in Spanish at the end of the presentation. She spoke about growing up in East Los Angeles as the daughter of Mexican immigrants from the state of Michoacán, about the murder of her cousin in 1996 and subsequently leaving Los Angeles for New York, about disconnecting from her family until nostalgia set in, and about starting @veteranas_and_rucas as a way for women to begin to heal from the violent crime that proliferated in the 1990s.

In Spanish, Rosales spoke slowly and with a smaller vocabulary than in English, repeating sentence fragments, looking occasionally to the museum staff for clarification and nervously ending her answers with the filler word ‘pues’ (‘uhm’ in English). After a few questions, a woman, who had entered halfway through the presentation, raised her hand. ‘You’re talking a lot about violence’, she said, in Spanish. ‘But the most fundamental site of violence is language. So my question is: since you speak Spanish, how dare you come to Mexico and present in English?’2

‘Hablamos después’, Rosales responded, ‘We’ll talk after’. The museum staff looked at each other nervously, but decided not to intervene. The anger on both sides was palpable, yet the tension in the room was ultimately the fault of neither person: rather, it was a reflection of the intractability between two groups who assumed they knew more about one another than they did – assumed that they were, in some way, more of one another than they were. On one hand, Rosales made a typically American mistake: assuming you can show up anywhere and be understood in English is, if not an act of violence, one of privilege. On the other hand, the audience member lacked the contextual knowledge to understand Rosales’s discomfort with Spanish: that in 1980s California, students were punished for speaking the language at school and placed in remedial or special education classes, and that the multiple jobs Rosales’s mother worked – not to mention her incarceration, which put Rosales and her sister in foster homes for several years – afforded the family limited time together to converse.

This article examines this intractability through analysis of two photographic projects that represent Chicanas in East Los Angeles: Rosales’s Instagram counter-archive @veteranas_and_rucas; and the series Cholos by the Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Rosales’s project was created in part as a response to outsiders’ representations of Chicanxs, and sets self-representation as a boundary circumscribing @veteranas_and_rucas. Iturbide’s photographs have been called ‘ethnographic’ and have also been critiqued by the communities she portrays. Yet despite the ways in which Iturbide’s photographs reify some of the stereotypes to which Rosales’s work reacts, her photographs of the Chicanx community of East LA have been accepted and lauded as sensitive and authentic when featured on @veteranas_and_rucas.

East LA, where Rosales grew up, is a toponym that refers to a group of neighbourhoods and municipalities in eastern Los Angeles County, of which the population is more than ninety per cent Latinx. The area became a refuge for Mexican immigrants starting with the mass dispossessions of the Mexican-American war; later, during the decade of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), more than 50,000 Mexicans fled to California.3 As a site of the Chicano Movement, East LA fomented the 1968 ‘Chicano Blowouts’ – a series of high school walkouts in protest of unequal conditions in the Los Angeles Unified School District – and the Chicano Moratorium’s largest march, a 1970 anti-Vietnam War demonstration that turned into a brawl with LA County Sheriff’s deputies, claiming the life of the Los Angeles Times columnist Ruben Salazar.4

In the 1990s, however, East LA became known for violence. The years 1988–98 are known as the ‘Decade of Death’ due to a city-wide homicide rate that reached 1,000 deaths per year.5 Rosales, born in 1980, came of age during this period. Two days before Christmas in 1996 her cousin Ever, who lived with her and her mother and sister, was murdered. ‘It was the first time I was exposed to violence in such a personal way’, Rosales has expressed, ‘even though I grew up having drive-by shootings in front of my house and knowing people who got jumped or arrested’.6 She fell into a depression that prompted an identity crisis and in 1999 decided to move to New York, despite having no connection to the city. She stayed for ten years.

Behind her impulsive decision, Rosales says, there was a conscious move to disconnect from her family and background. She joined queer art circles and never talked about East LA, knowing that her New York friends – artists who came from well-educated and financially supportive families – would not be able to relate. Eventually, nostalgia set in. Rosales remembered the parties she went to as a teenager, thinking fondly of the community they had fostered, and started to look at the collection of photographs she had brought to New York. She began to use the internet for the first time, initially to find out whether her LA friends were still alive. Then she learned that she could request the documents pertaining to her cousin’s death:

When they came in the mail and I opened them, I felt like I was close to his body again, like I went back to 1996. I got to revisit and relive that moment. It made me think, I miss that period of time, even though it was so violent. It was the first time I realised that a document was really important, that it tells a story.

Rosales called her sister for the first time in years. ‘I don’t want to talk about the nineties’, her sister told her. Other friends said the same thing: that the decade was best left in the past. Women, Rosales observed, had no masculine heroism about having lived so close to so much violence; instead, they carried shame heavily and silently. Her determination to find others who would talk about it culminated in the creation of @veteranas_and_rucas in 2015.

Within one week women had started to send photographs to Rosales’s anonymous email account. One woman wrote that she had a stack of photographs that she was about to throw away. Rosales visited her and they went through the photographs together, talking about their similar experiences. At the end of the afternoon, the woman gave the photographs to Rosales, with permission to post them. Another woman, who now uses a wheelchair (a consequence of having been shot), gave Rosales permission to post a photograph of her that shows a post-operative scar running the length of her torso. Eventually, even Rosales’s sister opened up.

To date Rosales has posted nearly five thousand photographs and @veteranas_and_rucas counts over 265,000 followers. Although the photographs are as diverse as the individuals they portray, they share aesthetic themes. Many of the women depicted wear hoop earrings and lip liner and use hairspray; others prefer white t-shirts and baggy Ben Davis workwear. Several of the photographs were taken at mall storefronts called ‘Glamor Shots’ and ‘Starshot Studios’ that were popular in the 1990s. With their pastel backgrounds and hazy resolutions, they resemble anti-school portraits, capturing the teenagers how they want to be seen: made up, wearing Dickies or Raiders jerseys, caressing a boyfriend or holding an infant. There are group photographs taken at backyard parties, poses with lowrider cars and flyers announcing car washes to raise money for the funeral costs of murdered friends. Many captions note that the photographs are submissions from the daughters, granddaughters or nieces of the women pictured. Other times, they commemorate an incarcerated friend or relative, or one lost to gang violence. Some submit photographs of friends with whom they have lost contact, hoping the account will help them reconnect.

In his essay ‘The power of the archive and its limits’ Achille Mbembe details the paradox of the archive: it is the name for both the documents that a state deems worthy of preserving and the building in which it stores them.7 ‘There cannot [. . .] be a definition of “archives” that does not encompass both the building itself and the documents stored there’, he writes. If there cannot be a definition of the archive that does not imply an entanglement between state power and memorialisation, then efforts outside of the state to do the same work – to convert certain documents into ‘items judged to be worthy of preserving and keeping’ – cannot be archives. This is why Rosales’s work constitutes a counter-archive.

Rosales’s aims also define her work as a counter-archive, as she sets out to challenge representations in the mainstream media and politics that portray LA’s Latinx immigrant and Chicanx communities as cholos, or gang members. She does not want to erase the reality of gangs, but to expand the narratives and representations possible for Chicanas and Latinas, and to humanise the gang-influenced reality in which she and others grew up: ‘If someone sends me a photo and they’re flashing gang signs, I’m not going to blur that out [. . .] I’m going to give them the platform to tell that story. This project is a way to dismantle the way we’ve been represented’.

The word cholo has a long and varied philology. It originates from the word Xolotl, an Aztec god of fire and lightning who took the form of a dog-headed man. In 1571 Alonso de Molina wrote in his Nahuatl vocabulary that the word ‘xolo’ meant slave, servant or waiter.8 In the Spanish Empire’s casta schema, cholo referred to the child of one mestizo (a person of combined European and indigenous American descent) and one indigenous parent, giving the word’s pejorative use a racial undertone.9

Most accounts trace cholo culture in the United States to pachucos, a subculture that originated in the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez area in the early twentieth century, spreading throughout the Southwest and eventually to LA.10 The pachuco style was marked by zoot suits – high-waisted, wide-legged trousers and long coats with wide lapels and padded shoulders. White onlookers racialised the style, culminating in the Zoot Suit Riots in 1943, when members of the United States military began attacking pachucos across southern California, claiming the excess fabric of their suits made them unpatriotic.11

Now, cholo means different things to different people. James Diego Vigil writes that in LA ‘many individuals copy the style without joining the gang’.12 Lionel Cantú agrees that it is ‘used to reference contemporary dress codes and hair styles seen in urban spaces that are associated with Mexican gang members’.13 The Tejana artist and writer Barbara Calderón sees it as an aesthetic derived from the styles of LA gangs.14 Yet Rosales argues that representations of Chicanx culture produced by outsiders elide the distinction, criminalising a culture by conflating its aesthetic with gangs. ‘If a person of colour is wearing baggy clothes in East LA’, she says, ‘a lot of people automatically think they’re involved in gangs. But that wasn’t what most of us experienced – it was a style. If I saw a kid with baggy pants and a hoodie, to me that was a partygoer. But others have already decided that’s a cholo – that person has already been put in a category they don’t belong in’.

The way in which gang violence and death influenced the creation of @veteranas_and_rucas also coincides with Mbembe’s analysis of the archive. ‘Examining archives is to be interested in that which life has left behind, to be interested in debt’, he writes. ‘[The archivist and the historian] maintain an intimate relationship with a world alive only by virtue of an initial event that is represented by the act of dying’. Though many of the women pictured in @veteranas_and_rucas’ posts are still alive, Rosales’s counter-archive nonetheless recalls something that has passed: previous eras of Chicana life in East LA, with all the aesthetics, modes of relating and forms of violence that they implied.

By creating this counter-archive and platform for Chicanas to tell their own stories, Rosales interrupts the assumption that certain aesthetics signal criminality. In turn, she uplifts the ephemeral traces of quotidian Chicana life into documents worthy of preservation and displays the breadth and richness of the community’s history.

Una chilanga en East Los Angeles

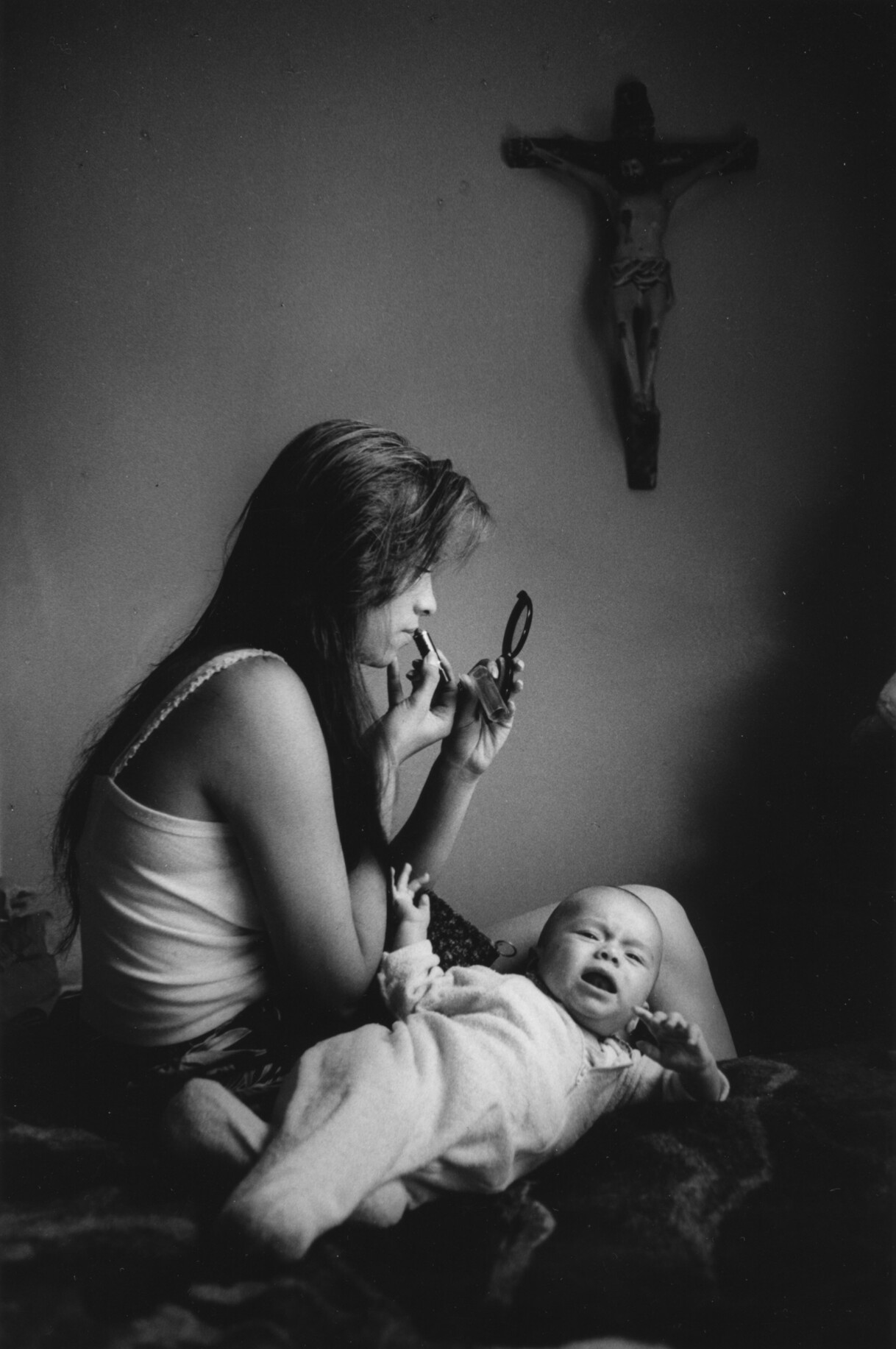

In 1986, as gang violence was escalating, the Mexican artist Graciela Iturbide travelled to East LA to photograph Chicanxs. Invited to participate in the project A Day in the Life of America, Iturbide decided to photograph the Chicanx community because she ‘wanted a book about life in the US to include a marginal community such as theirs’.15 The Chicana artist Isabel Castro put Iturbide in contact with El Centro La Raza, Los Angeles, where it was suggested that she photograph cholos specifically and brought her to meet members of the White Fence Gang FIG. 1.16

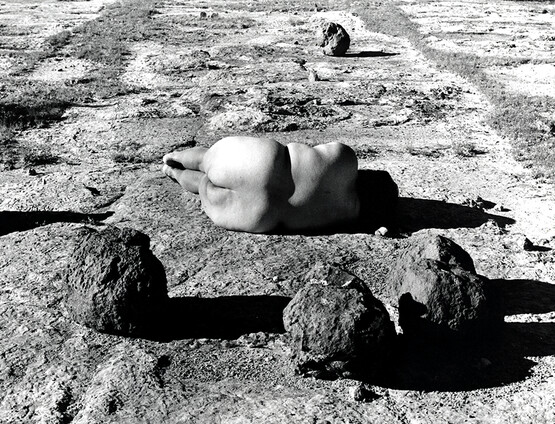

Born in 1942, Iturbide grew up as the oldest of thirteen siblings in a wealthy Mexico City family.17 In 1970, following the death of her six-year-old daughter, Iturbide began working as an assistant to the photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo. She has since become one of Mexico’s most celebrated photographers, particularly for the way her work depicts the diversity within Mexico, especially its indigenous communities. Iturbide’s first major project, funded in 1978 by Mexico’s National Indigenous Institute, followed the Seri, a semi-nomadic group in the Sonoran Desert, who were undergoing a process of sedentism. The project resulted in the 1981 photobook Los Que Viven en La Arena (Those Who Live in the Sand), for which Iturbide collaborated with the anthropologist Luis Barjau FIG. 2.18

The work that cemented Iturbide’s place as a major Mexican photographer and brought her international acclaim, however, is the photoessay Juchitán de las Mujeres (Juchitán of the Women), published in 1989 but comprising a series of photographs taken from 1979 to 1986. The series documents Zapotec women in the titular location, a city in the Isthmus of Tehuanepec region of Oaxaca, with accompanying text by the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska.19 The photographs include Magnolia con espejo (Magnolia with a Mirror), a portrait of a muxhe (a Zapotec third-gender individual) FIG. 3; El rapto (The abduction), which shows an adolescent girl lying on a bed, showered with flowers after passing the ‘virginity test’ – a tradition present in the Isthmus culture FIG. 4; and Nuestra Señora de Las Iguanas (Our Lady of the Iguanas), perhaps Iturbide’s most famous photograph, which depicts a woman crowned by seven iguanas FIG. 5.

Although the Juchitán photographs generated international attention, they have also sparked debate over Iturbide’s representations of Zapotec women. Some critics and anthropologists have argued that Iturbide’s work is ethnographic. Traditionally defined as the systematic study of cultures, ethnography is a key method and approach in anthropology. In contemporary usage, the term implies embeddedness, informed consent by – and sensitivity to – one’s research subjects and self-reflexivity. The art critic Cuauhtémoc Medina wrote that ‘Iturbide belongs to a generation of Mexican and Latin American photographers who reactivated a passion for the discipline in the 1970s and 1980s, mostly from within so called “ethnographic photography”’.20 The anthropologist Stanley Brandes writes that Iturbide’s work raises questions that are of interest to anthropologists – for instance, gender, ritual, religion and death – and considers her an ‘innate anthropologist’. He notes that the Juchitán photographs not only ‘illustrate ethnographic reality’, but have ‘worked as well to shape perceptions of Zapotec society, especially with regard to gender’.21

It is precisely this influence, however, that has sparked responses from other anthropologists and Zapotec women critiquing Iturbide’s representations of the women of Juchitán. Tracing the history of outsider representations of Zapotec women, Howard Campbell and Susanne Green argue that Zapotec women have been portrayed as hypersexual, ‘matriarchal’, ‘Amazon-like’, and ‘mysterious and powerful’ since the sixteenth century, and that visitors’ accounts often reiterate stereotypical content from previous descriptions written by outsiders.22 Such tropes include Zapotec women running markets, wearing traditional clothing and dancing. Campbell and Green argue that Iturbide’s and Poniatowska’s book not only reinforced these stereotypes, but brought them to an international audience FIG. 6.

Zapotec women have expressed similar sentiments. Ofelia Ruiz Campbell writes: ‘Because of their short stay in the area, outsiders [. . .] leave with the impression that Zapotec women are Amazons or that they live in a matriarchal society, when the reality is quite different. The foreigners [. . .] romanticize it, exaggerating particular dimensions of reality, depending on their personal interests’.23 The Zapotec anthropologist Edaena Saynes-Vázquez argues that the stereotypes presented by outsiders remain present only in lower social classes of Zapotec society: the topos of the market woman, for instance, makes sense because the market is a space accessible to foreigners. However, she writes, market work is a low-income activity associated with low social status; market women therefore represent only a limited slice of Zapotec society.24

Saynes-Vázquez’s article also recounts a conflict over Iturbide’s representation of the community. Doña Marcelina Cerqueda, who appears in one of Iturbide’s images, seated in front of an altar holding a painting of herself, responded when the photograph was published that ‘she had posed for her friend Graciela, and did so with pleasure, but it was not pleasing at all to see that photograph published, with her dressed informally, holding up a painting that she does not like’.16

Similar to that of an ethnographer, Iturbide’s work derives credibility from her intimacy with her subjects.26 Yet in this case, the subject’s story reveals the way an outsider’s pursuit of a certain aesthetic can project ‘orientalising’ assumptions onto their subjects, in turn reducing the breadth of their reality. Saynes-Vázquez writes: when ‘outsiders argue for an egalitarian Zapotec society or for a society ruled by women, Zapotec women say: galá n pa dxani (that would be great it if were true)’. Juchitán de las Mujeres, she writes, is ‘magical realism’.27

Iturbide does not aim for her photography to be ethnographic: ‘photography is not truth’, she writes. ‘The photographer interprets reality and, above all, constructs [their] own reality according to his own awareness or his emotions’.28 For her, the artistic composition and the way that a photograph can become a world of its own, is most important. The writer Carlos Monsivaís affirms Saynes-Vázquez’s ‘magical realism’ critique, but instead sees it as a positive aspect of the work, writing that Iturbide’s photographs contain ‘echoes of surrealism and the abstractionists’.29

Iturbide’s photographs of East LA focus on a group of cholas called the White Fence Gang. Although little has been written about this series, the majority of responses celebrate the sensitivity of the photographs. Like Brandes, Nadiah Rivera Fellah considers the East LA series to be ‘anthropological in nature’, noting that the photographs ‘construct a space where the cholas are no longer circumscribed by discriminatory perceptions or marginalization’.30 Luis Hernández writes:

Iturbide managed to simultaneously inhabit and subvert the stereotype of Mexican-American criminality, making their intimate sides public and showing the humanity of gangsters who also raised children, who showed off their zoot suit heritage [. . .] who felt proud to belong to a community that is reviled from the outside, but that takes care of its own.31

One interesting way to conceptualise the photographs ethnographically is to place them in the geography of Iturbide’s corpus. If one considers her body of work an ethnographic exploration of the many cultures of Mexico, then East LA becomes, effectively, a region of Mexico, and Chicanxs a cultural group within it.

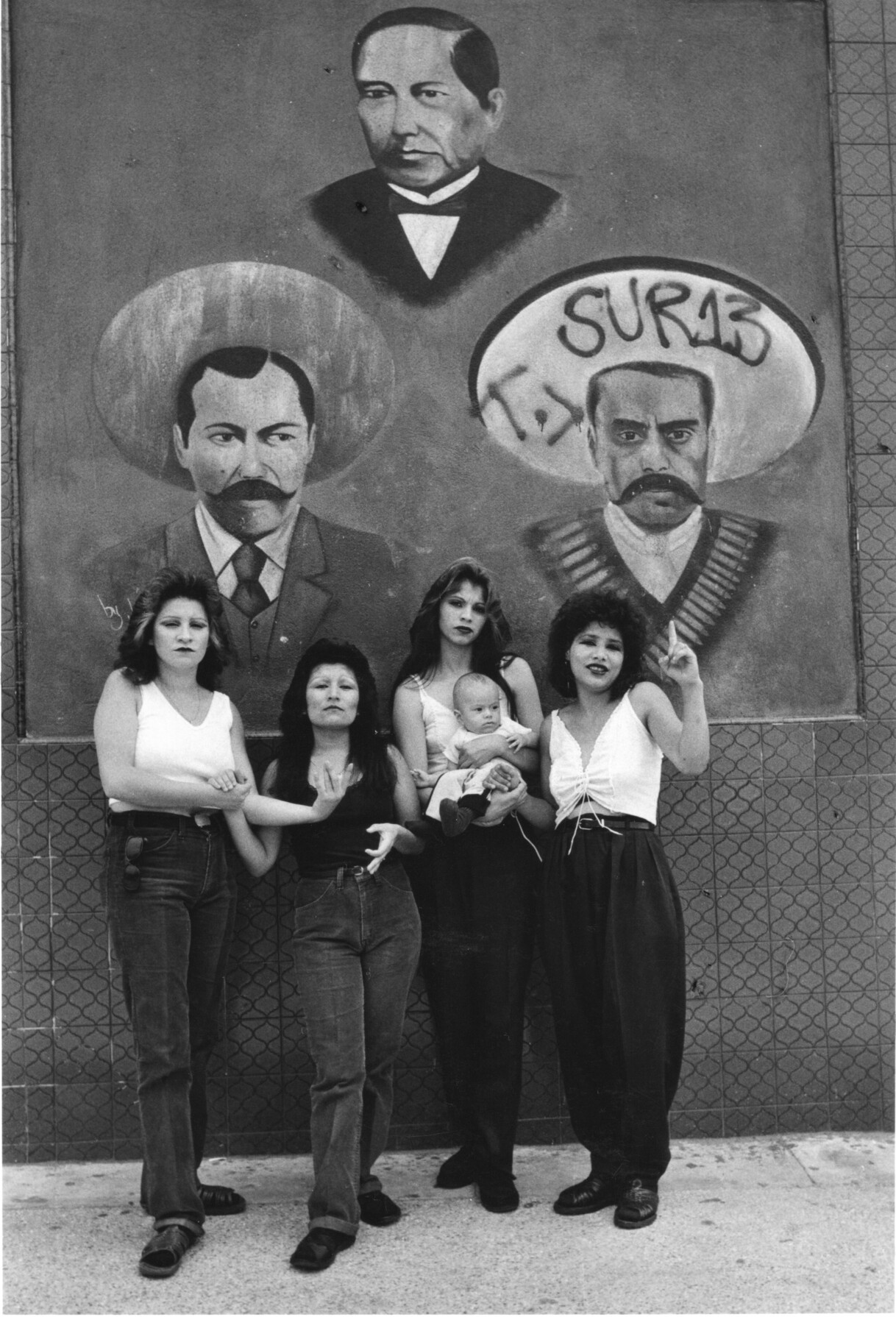

Iturbide’s photographs share certain aesthetic sensibilities with those that Rosales posts on @veteranas_and_rucas. In Cholas I (con Zapata y Villa), White Fence, East LA for instance, the women flash gang signs and wear dark lipstick, one holds a baby FIG. 7.

Yet with Rosales’s critique of outsider representations of Chicana and Zapotec women’s views on Iturbide’s work in mind, the images and their reception begin to play into Mexican stereotypes about Chicanxs. The subjects in Iturbide’s photographs do not appear to show off their ‘zoot suit heritage’, as Hernández writes; rather, it seems more likely that the zoot suit riots are Hernández’s only reference point for Chicano culture and history. Nor do the photographs suggest a sense of being reviled from the outside; if anything, there is an insularity to the images, or a self-referentiality in which the subjects defined themselves in relationship to other gangs.

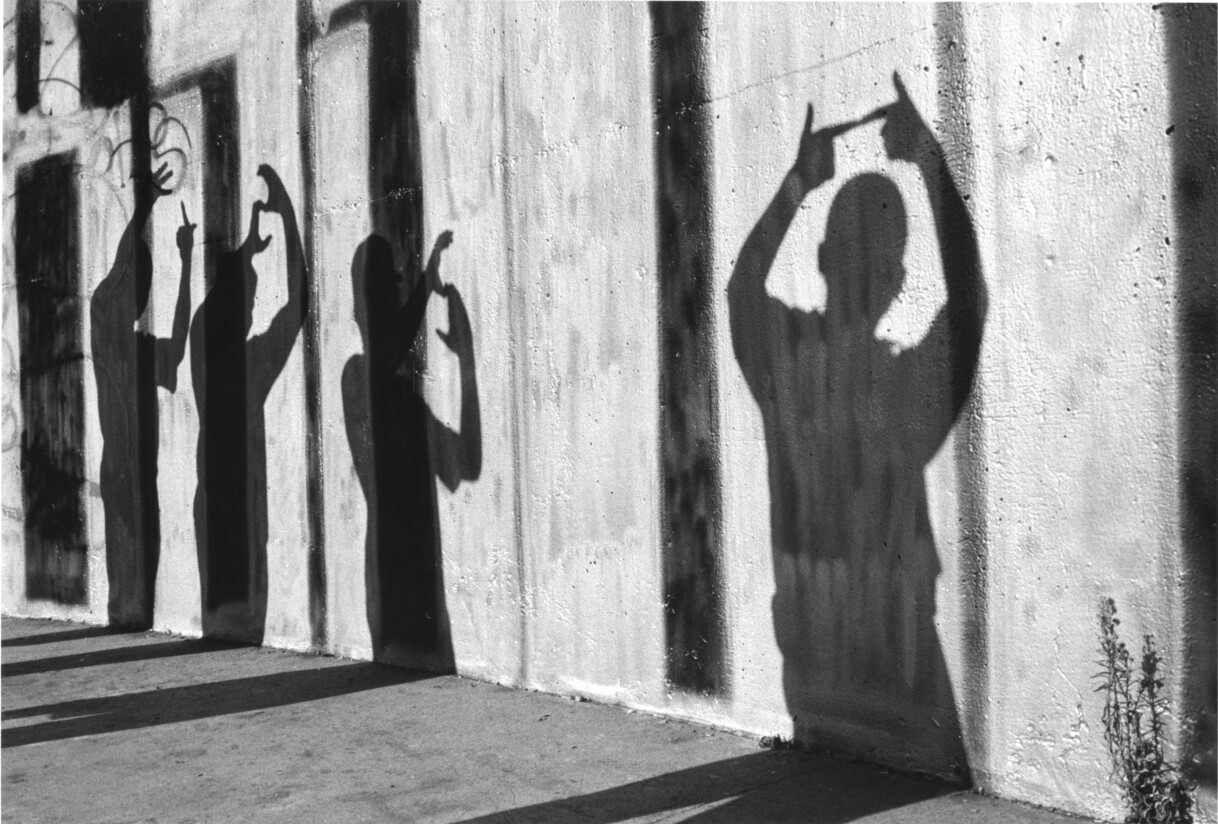

Moreover, there is the decision to specifically photograph gang members, which does little to subvert the idea that all Chicanxs belong to gangs. The image Cholos, White Fence Gang FIG. 8 shows the shadows of the subjects’ hands projected on a wall, reducing each individual to the signifiers of their gang. However, in reality, all the members of the White Fence Gang photographed were deaf. This layer of disability is invisible in the images and might prompt consideration of the members’ so-called ‘secret hand signs’ as distinct from those that exist solely to demonstrate gang affiliation.32

This emphasis on Chicanxs as cholos is important not only in the United States but also in Mexico, where cholo is also a stigmatised identity with a variable definition.33 The various interpretations of the term are united by their shared imagined aesthetic defined by American influence and violence. One interviewee remarked to the present author: ‘it’s the Chicanos who speak in Spanglish’, implying low levels of education and assimilation into US culture. Another noted that she used the term more to describe ‘the gangs here in Mexico City [. . .] people with aesthetics close to the Chicanos, from low-income neighbourhoods, low education level [. . .] men who are clearly living at the edge of the law’. This definition implies that this marginality is the societal position of all Chicanxs, something that Iturbide’s work reinforces. As in Campbell’s and Green’s argument that outsider representations of Zapotec women build upon one another to reify stereotypes, so assumptions about Chicanxs as cholos are reified through the accumulation of repeated tropes FIG. 9.

Iturbide also reifies the commonplace notion that Chicanxs are ignorant of Mexican culture, an extension of the idea of betrayal that animates much discrimination against Chicanxs by non-migrant Mexicans. For example, in Cristina tomando fotos en Los Angeles, Iturbide pictures her subject in front of a tortillería named Cuahutemoc, which is a misspelling of Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor. This appears in large, unobstructed lettering in the background of the photograph, unmissable to Mexican viewers. Iturbide’s framing highlights a Chicanx ignorance of Mexico. This is compounded by an interview Iturbide gave to the Los Angeles Times:

They [Chicanxs] have a nostalgia about Mexico that isn’t always based in fact. A group of them told me, ‘We want you to photograph us by the mural of the mariachis’. And it was a mural of Mexico’s historical heroes: Benito Juárez, Pancho Villa. They can be really mistaken about Mexico, but they still have a profound nostalgia for it.34

In this short extract, Iturbide repeats the word nostalgia twice. The use of the word suggests that she sees Chicanxs’ relationship to Mexican culture as one of looking back, rather than as a present engagement with the country and the ways its culture manifests in the United States. Chicanxs who grew up going to US public schools can hardly be blamed for not being able to correctly identify historical Mexican figures. Moreover, it seems possible that the desire to be photographed in front of ‘the mural of the mariachis’ is not a nostalgic one: in the United States, Mariachis serve as a metonymic symbol for Mexico, despite the fact that in Mexico they are associated specifically with the state of Jalisco. Additionally, another gang had already tagged the mural, suggesting perhaps a second motive of reclaiming the space through being photographed there.

Like the altercation at the Museo del Chopo that began this article, Iturbide’s photographs betray the way that Mexicans and Chicanxs often assume they know more about one another than they do. Considering the aforementioned critiques of Iturbide’s work, her photographs of cholos begin to appear less as a sensitive representation of Chicanxs and more like a representation of the way that Mexicans presume them to live.

Chicanas on Instagram

Campbell and Green argue that stereotypical accounts of Zapotec women need to be challenged by ‘more compelling and perhaps more accurate representations – representations that we suggest will come from Zapotec women themselves and hopefully anthropological research’.35 Their emphasis on the need for Zapotec narratives resonates with Rosales’s emphasis on self-representation in @veteranas_and_rucas. These ethics and calls for self-representation in turn resonate with the scholar Eve Tuck’s ‘Suspending damage’, a request for communities under study to suspend their cooperation with researchers in order to set boundaries that will protect them.36 By creating a photographic counter-archive by, and predominately for, Chicanas themselves, @veteranas_and_rucas takes representation into Chicana hands and sets self-representation as a prerequisite.

On 25th August 2020 Rosales posted a colour version of Cholas I (con Zapata y Villa), White Fence, East LA to @veteranas_and_rucas. She wrote the caption:

This photo of Las Sleepy, China, Smiley, Tiny [from] White Fence Tiny Monstras gang was taken by Graciela Iturbide in 1986, right on the corner of Camulos and Whittier Boulevard, in front of Odono’s Meat Co [. . .] If these streets had a voice (which in some ways do), they would tell us endless stories-Our experiences leave markings. On every hidden corner, every alleyway, every street and in every home we continue to exist even after we are no longer physically here. We map this city through our stories and images. RIP to Lisa who passed away in 2018.37

In the same post Rosales included two photographs of the Boyle Heights site of the ‘Mariachi Mural’ today. They have a wider angle than Iturbide’s photographs and a blue Google Maps pin reveals them as screenshots from that platform. The first shows that the mural has been painted over in beige, and the surrounding red tiles in burnt orange. The second, taken around the corner, shows the front of the building: a boarded-up storefront with a fading, cracking sign that reads ‘Odono’s Meat Co’, covered by a ‘For lease/Se renta’ banner.

The post gained over 21,000 likes and numerous comments written in English and Spanish. One commenter wrote, ‘I’m floored seeing the Odono’s Meat Co. My mother dated Ray Orozco. He was one of the owners. I was in junior high at the time. We lived on 3rd and Arizona. Our house was in Marianna Maravilla territory’. Another said, ‘Damn down the street. That mural was there for so many years’.

Many recognised the women in the photographs. One tagged a friend and wrote, ‘that’s ur sis Vicky?’ Someone else replied, ‘yes that’s [Vicky’s] sis n Vanessas mom next 2 her, I know the first 3 but not the last one, I think it was VICKY’s aunt who took the pic’. Another young woman wrote that Lisa, ‘La Sleepy’, was her mother:

She passed away in 2018 her birthday is this Thursday crazy story graciela iturbide got in contact with my mom 32 years after this picture was taken [. . .] to see how she was doing all those years later not knowing my mom was battling stage 4 cancer glad she was able to take some beautiful pictures once again weeks before my mom passed.

The comments reveal that Iturbide’s photographs have a powerful afterlife in East LA’s Chicana community, here manifesting as artifacts so beloved that they are confused for family candids, while those who do know their authorship look favourably upon Iturbide’s presence: ‘What an artist. She always capture the deep essence soul of the culture’.

One interpretation of this warm reception of Iturbide’s work is that the ignorance she diagnoses in Chicanx works in her favour: her subjects see her as one of them, despite Mexico’s vast class disparities and the differences in culture that they imply. However, a more powerful reading is that perhaps the artistic composition of Iturbide’s photographs helps grant the community the ‘privileged status’ – to recall Mbembe’s term – of archivability, an end that is in line with the goals of the @veteranas_and_rucas counter-archive.

The comments also demonstrate that nostalgia is indeed part of the Chicana narrative. The revelation of Lisa’s death and the boarded-up storefront speaks to Rosales’s aim of celebrating Chicana culture and memorialising violence. But the comments show that it is not nostalgia for a poorly understood Mexico, as Iturbide understands it. It is nostalgia for LA and for the Chicanx community. This is the nostalgia that animated Rosales to start @veteranas_and_rucas: her longing for 1990s LA and its unlikely emotional coexistence of grief, vengeance, solidarity, isolation, creativity, shame and pride.

The afterlife of Iturbide’s East LA photographs aligns well with her perception of the work as an aesthetic fabrication, focused on formal qualities over ethnographic ones. The poetry and emotional reality of her images have enabled the community to claim and shape them as their own, long after Iturbide left town. The failure of the images as ethnographic, then, allows them to be folded into Chicana narratives and to confirm Rosales’s mission of self-representation. The artistic nature of Iturbide’s images grants a status of archivability that extends beyond the photographs’ frames. And the afterlives of the images demonstrate that it is not only representation itself that matters, but also the reclaiming and reframing of those representations made by outsiders.