In the age of artificial intelligence (AI), robots have learned how to paint like Van Gogh, compose music and create original portraits.1 Exhibitions that explore AI’s artistic capabilities have recently exploded in popularity, relying on a compelling but ultimately shaky binary that pits human ingenuity against that of ‘the machine’. For Joanna Zylinska, AI art is not necessarily a captivating case study of the ‘othered’ robot imitating human creativity with increasing skill. In her book AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams (available in print and as a free, open access PDF) she proposes instead that human creativity has always, at its core, been ‘technical and to some extent artificially intelligent’.2 She examines the ways in which focusing on the aesthetics of AI art can in fact serve as a distraction to deeper, more immediate ethical questions in the discipline: how can artists use their unique position as agents of wider socio-political contexts to substantiate the possibilities of AI? Why is it necessary to discuss AI in conversations about the global climate crisis or exploitative labour practices? How does AI subvert the idea of creativity as an intrinsically human trait?

Zylinska dismisses much of the current hype surrounding AI, instead framing it in an art-historical context. The book’s main strength lies in its surgical precision; where other publications have already heralded the dangers of unchecked AI to a non-specialist audience, this investigation dissects arguments from art-world residents, ethicists and technologists with a laser-sharp focus. Zylinska invokes post-humanism as the book’s predominant ethos, referencing technology-focused philosophers such as Vilém Flusser to assert an art-historical theory in which the idea of human-derived creativity is stripped away to reveal the ‘plethora of nonhuman agents’ that influence any of our given actions – from drugs and devices to external networks and cultural pressures.3 As an example of her post-humanist framework, she proposes the artistic concept of ‘undigital photography’, which builds upon her earlier theories of photography as a practice born from partnerships between human and non-human elements – such as the automatic processing of raw files by digital cameras or the wider cultural algorithms that affect our creative decisions.4 These elements continually influence each other, and yet as the boundaries between them fluctuate the question of human agency becomes paradoxically more central. Through this analysis Zylinska mirrors many questions in current AI practice, where the eroding binary of human versus mechanical responsibility is even more apparent.

Zylinska also expresses frustration with what she categorises as visually engaging but ultimately superficial ‘Candy Crush’ AI art. Work of this nature is primarily focused on the experience of looking, using images of deconstructed body parts or morphing colours to propose new forms of humanist representation. Her criticism is directed at artists using AI technologies, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs), only to become trapped in an endless cycle of performative productivity. As examples she cites Mario Klingemann’s surreal portrait series Superficial Beauty (2017) and Mike Tyka’s Portraits of Imaginary People FIG.1, comparing their work to commercially creative tools, such as Google’s DeepDream software, which offer ‘art as spectacle’ without much substance.5 Interestingly, Zylinska does not prioritise the valuable ability of these works to recontextualise our conceptions of art in a digital age or establish emerging mediums as artistic tools – two concerns that have long been pillars of art-historical discourse. However, in an art world now familiar with shifting patterns and uncanny depictions of human forms, she does rightly identify that ‘uncritical instrumentalism' – or the use of tools without the ability to account for differences that matter – has become a defining quality of some works that have more in common with normative and corporate AI trajectories.6 An AI portrait does not just consist of two eyes, a nose and a mouth, as companies like Google and Generated Photos indicate. It also encompasses thousands of invisible, algorithmic decisions, some of which can become political when they lead to unequal representation of skin tones or the erasure of disabilities, due to a lack of diversity in the data set.

In chapter 8 Zylinska counters these ‘Candy Crush’ creations with the work of Trevor Paglen, who primarily uses humanistic motivations to reveal AI’s operative networks – some of which have real effects on our everyday lives. For his work It Began as a Military Experiment Paglen used an algorithm to place small letters on features of faces selected from the Face Recognition Technology (FERET) database. He codified these portraits in the same way that modern facial recognition technology did during its initial development, albeit with the new intention of increasing data transparency FIG.2. The artist’s efforts to crack the lid of AI’s inscrutable ‘black box’ invites the public to directly confront the real human faces from which a ubiquitous but controversial tool was built. By examining the wider infrastructure of AI to tease out the roots of issues such as data bias and surveillance, Paglen prioritises AI’s undeniably human impact over the allure of pure aestheticism.

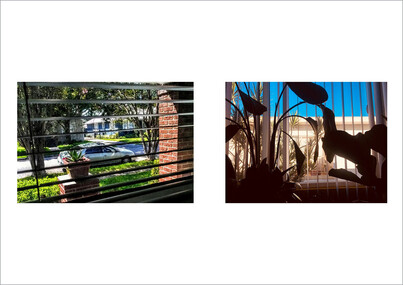

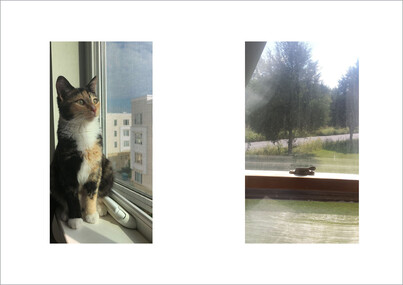

Throughout the book, Zylinska frequently references the potential of AI art to both mirror and influence the world’s social, political and cultural networks. Early on, she relates artificial intelligence to another ‘AI’: what she calls the ‘Anthropocene Imperative’, or the need to ‘respond to those multiple crises of life while there is still time’.7 For Zylinska, works like feminist collective voidLab’s Shapeshifting AI (2017) FIG.3 and Shadow Glass (2017) FIG.4 expand the discourse beyond the solutions for societal inequalities promised by commercial AI peddlers.8 In these projects, voidLab has taken audio from interviews they conducted concerning our world’s hidden threats, such as technological redlining, and set them to hallucinogenic visuals of animated figures and fractals.9 Although initially Zylinska introduces the Anthropocene Imperative as an issue of climate change, she pivots her concerns in the latter half of the book to works of art that investigate additional social dangers. Looking at Lauren Lee McCarthy’s project LAUREN, in which the artist attempts to become a human version of Amazon’s Alexa, Zylinska examines the erosion of privacy and identity via smart home assistants FIG.5 FIG.6. Turning to her own video work View from the Window, Zylinska addresses the depersonalisation of digital labour in marketplaces such as Amazon’s crowdsourcing platform Mechanical Turk (MTurk) FIG.7 FIG.8. Overall, Zylinska covers an ambitious number of topics and creates a compelling argument: in order for AI art to be most effective, it must confront our entanglement with the wider networks, systems, and imbalances that surround us.

Today, AI does not solely reside in the domain of wires and screens. It is intimately tied to the human experience, stemming from all manner of invisible, system-wide forces. AI art, as both an exploration and a product of those forces, is not a passive agent of change to be reduced to pure aestheticism. It can raise timely investigations about who art is for, what will happen to our world and even about the very nature of intelligence. After all, from a post-humanist perspective, we are all to some extent artificially intelligent, but it is the questions we ask with that intelligence that truly matter.